|

4. The Work Force

Many

complained that the pay was low; but it was regular and better

skills bought better pay. The record of just how many put in year

after year of service, the job satisfaction speaks for itself. A man

who had nothing to thank his factory for would most certainly not

recommend to his

offspring that they should find employment where he worked.

That the Gibbons factory had sons, fathers and grandfathers

working at the same place at the same time did show that the old

adage of "if you know a better hole, go to it" was well in

mind.

With

so many faces and individuals in memory, before continuing about who

they were and what they did at Gibbons as a family of workers, while

one’s memory flicks from one thing to another, there is a part of

Gibbons history, which though not of great importance to some was,

at the time, of great

importance to the work people involved.

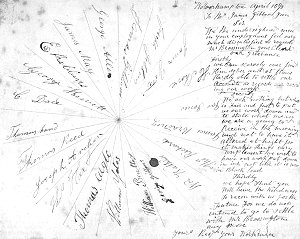

In the factory records was a sheet of paper about 9 inches

square. It was a

"Round Robin", made up of names in a circle radiating like

the spokes of a wheel so that, unlike a list, no name appeared on

the top to suggest who was first to put his name to the complaint

and thereby invite retribution as the ringleader.

The round robin |

The text reads: "We the undersigned

men in your employment feel very much dissatisfied as

regards Mr. Brassington your clerk. Our grievance,

firstly, we can scarcely ever find him sober and at times

hardly able to settle our accounts as regards our reconing

(sic) our work Secondly we aks nothing but what

is fair and just to put us our work down and to state what

money we are going to receive in the morning and not to have

it altered at night for it makes things very

unpleasant. We wish to have our work put down in ink

not like it is now in black lead. Thirdly we hope that

you will have the kindness to recon (sic) with us for the

future. For we do not intend to go to settle with Mr.

Bassington any more. Yours resy your workmen". |

In

those earlier days, the factories had a "Works Foreman"

who could hire and fire on behalf of the boss. Like a regimental

sergeant major he patrolled the factory to keep order and see that

no one slacked on the job. An important part of his duties was to

hand out the pay to his charges on Friday night or Saturday.

He would know who had done what and how much was due to

individuals. Having

paid out there would sometimes

be a little left, which went into his pocket.

It would appear that one such gentleman had long pockets as

some of the workers found out when they felt that they had been

diddled. Thus it was that the Round Robin was sent to the owner of

the factory, the old Mr James Gibbons, imploring him to do something

about the erring foreman. What

happened about this complaint is unrecorded but this wonderful part

of factory history sticks in the mind of one who held it and read it

before it was lost forever in clear-outs that followed the

takeovers.

|

Staff of the Machine

Shop, 1948. |

Examples

of the pride that the workers had in what they produced could

sometimes be seen when away from the workbench.

The little chap whose job was to assemble "penny door

locks" for municipal toilets would, when on his week’s

holiday at the seaside, try every door lock in a row to see that

they were working alright, carrying a store of pennies for the sole

purpose. He would

despair at having to dismantle some, to remove washers or buttons

that had jammed the mechanism, so that these door locks stood

between the discomfort and comfort of anyone with a problem whether

a big one or the even bigger one of no small change.

| A Sales Conference -

company directors and the sales force met at the Sports and

Social Club. |

|

Back to a few individuals who come to memory.

Jack

Wharton, the supervisor of the Spring Door Shop, would occasionally

be seen pushing a plate glass door wide open just to see it return

to the closed position, calculating how long it took. Like so many others he was described as a "Gibbons

man", one who would have the good name of the firm in his mind

at all times. Later a

new product of skinning over aluminium with stainless steel sheet

for shop fronts and offices was added to his responsibilities.

For this he had to learn to drive so he could get to

customers. This, at a late stage in his employment, caused him some

apprehension but he managed it, after much practice on the works car

park on Saturday afternoons and Sundays.

James

Gibbons fame in the industry of lock making owes much to one family

in particular: the Robbins family.

I do remember Arthur Robbins Senior and his son Arthur

Robbins Junior. This family descended from other older members of

the family of three generations of locksmiths, whose skilled

expertise will still be found in locks across the country.

Young Arthur possessed a lock with a tiny key.

Made from two threepenny silver bits, it worked like a watch

smaller than a small thumb nail.

It could well be that the photograph that appears in old

catalogues of a lock maker at his bench is one of the famous Robbins

family. He may

have started at the age of twelve in the workplace, as this was

normal at that time until the school leaving

age rose to fourteen.

Ike

Timmins was the foreman of the plating shop and in charge of the

"bronzing" of brass work.

Bronzing changed the appearance of polished brass to look

like bronze. A chemical powder was mixed with ammonia to a thin paste,

painted on to the highly polished brass and allowed to dry.

Long hand brushes were then used to buff the object, which

would then have the appearance of solid bronze.

The stained brass retained its colour by polishing only with

furniture wax. A

kindly, religious man, Ike

was of the working gentleman school, who never swore or cursed -

though if really pushed his description was: a

"thundering" thing. One of his achievements in his plating trade was to produce a

"matt" (satin) plating that looked like silver and never

needed polishing. The

only pair of Gibbons candlesticks that ever received this treatment

stand on my mantleshelf, a tribute to his skill and valued

friendship.

Vic

Shermel, a small, rotund man, was the engraver of decorative

figures, door handles, plates etc.

An artist in metal, his different hammers and chisels worked

on the dressings after casting in brass and bronze. Sometimes he

worked by oil lamp to ease his eyes from constant attentive looking

at small work engraving, expensive lock plates and door knobs.

The designs for these would have been drawn up by an

architect, knowing that the Gibbons work force would do justice to

them.

Sir

Gilbert Scott and Sir Christopher Wren are remembered by the

buildings and their contents but little thought is given to the

lower end of the exercise, those who worked and produced or built

them. Much of the

skills of such men as Vic Shermel have been lost forever with

progress and the need to produce cheaper and quicker builders’

requirements and hardware; when wages were low, time could be

allowed for beauty and perfection

but that is not the case today.

Gibbons

had a strong ladies work force at Church Lane.

They came during the war and carried on at the lathe or drill

afterwards, accepted as equal if not paid the same rate of pay -

that came later in British factories.

|

Ladies and Gentlemen of

the Press Shop. |

Quite

a few of these ladies worked in the Machine Shop.

The Setter Up was a man named Albert Lycett. Albert would look after the lathes and drillers operatives,

mainly women, who were not averse to giving him the blame if the now

old lathes started to play up after years of war work.

As nice a man as one could meet, Albert married one of his

flock, "Vicky", then on retirement lived in Milton Road,

Fallings Park. He was a member

of the Rifle Club and helped to dismantle a former hospital ward at

RAF Bridgnorth, which was transported by the firm’s lorries and

erected at the Sports Club on the Birmingham New Road. A popular and

lovely couple who had a good word for everyone, now long gone but

remembered with affection.

After

the second world war former workers returned to the factory after

demobilisation. One who hadn’t work at Gibbons however, was a

former RAF stalwart. Sgt.

Stan Lane was the commissionaire.

Many an R.A.F. "sprog" (or recruit) would remember

Stan Lane. He was the

Station Provost Sgt. at R.A.F. Cosford during the war, though having

joined the RAF as a boy saw service in the desert of Arabia with a

Rolls Royce Armoured Car section.

When war broke out he was on Fighter Stations during the

Battle of Britain and was then posted to Wolverhampton’s RAF

Cosford. His first job

after demob was as commissionaire at Beattie’s shop in

Wolverhampton. He was

poached and his domain was the Time Office next to the main offices.

Until retirement he lived in a part of Ruckley Grange. This was owned by Mr Harry Attwood, the agent for the Rolls

Royce and Bentley cars. His

garage was at the top of Stafford Street.

In his job Stan was a typical service type of the old school,

firm but fair. Old

employees visiting the factory he tolerated up to a point,

but too many visits and you had to meet your former workmates

in the street outside after hours.

Just a little thing of the memory of Sgt. Lane, was his

boots. Rain or snow,

they had a shine like mirrors. One could imagine a recruit standing in front of them,

hypnotised and wondering what his fate would be for catching the eye

of the Provost Sergeant. But

his bite was by far worse than

his bark.

The

assistant in the Time Office was Sam Challenor. One could never forget Sam, a sense of humour with a store of

jokes, and stories that beggared belief.

A Bilstonian, he was as proud of his roots as a landed lord,

never ashamed of his accent though at times he emphasised it a

little. In charge of

the time office teapot, his dulcet tones could be heard half way

round the factory, "Tays med, ‘tis med"

What a character! He

did not fully appreciate the large influx of new arrivals coming

into the country at that time, before such opinions were suppressed

by law on the fear of death.

Sam had served as a soldier and he fully thought that he had

earned the right of free speech and gave full vent to it. On

retirement Sam became chairman of an Old Folks Club along the

Birmingham Road and was sadly missed on his death, for his

dedication to others as well as his family of "Challenors".

Simon

Perry came to Gibbons from the firm of Cyrus Price the safemakers.

The story of

this most honest and remarkable man has been told in the Black

Country Bugle by the man who had the job of taking him round the

country by car to open safes. He was a master "Cracksman"

whom it is known, from the records that were in the

firm’s offices, had never been beaten when opening a safe.

His forte was that after he had opened an offending safe he could

leave it just as secure afterwards, without destroying it with the

"cracking" open procedure of drilling around the lock.

| New people joined all

the time and mostly they stayed. Here is the first

intake of apprentices. |

|

So

many names, so many products that would take volumes to write about

and do justice to these people, what they made and how they lived,

their joys and sorrows that would

see a hat passed round to help in situations that

arose again and again. A wedding, a birth, a retirement a

death, people giving what they could in the days when hand outs from

the Government were far from the norm that it is today, for anyone

albeit having been in the country but a few days. That small

contribution was received gladly from workmates who knew from

experience that the little extra was oh so well needed.

On

another page (linked at the bottom of this page) there are

photographs of as many other members of the staff who were there in

my time as I could find photos of. All of them, and all those

not mentioned here, deserve to be remembered as individuals and as

members of a great team.

|