|

Wolverhampton started life as an agricultural settlement, boosted by

becoming an ecclesiastical centre, and then becoming a market town

providing not only a market but, almost certainly, a range of other

services as well. It may be that it was this agricultural connection that

first led to the metal bashing and engineering industries appearing here,

for not only would Wulfrunians find a living in selling clothes, shoes and

other necessities to those who came in to market but they would also be

able to sell agricultural implements. Certainly they did not start this

kind of work because coal and iron and limestone were found within the

borough boundaries. They were not. But they were close enough at hand for

enterprising people to be able to exploit them.

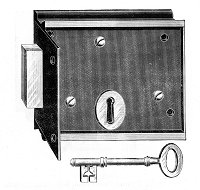

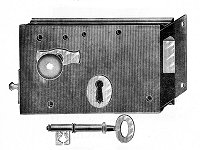

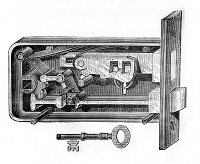

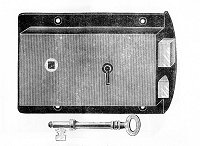

Although locks of some sort had been used throughout history, changing

social conditions and aspirations, increasing wealth and capital

accumulation, a change from community to individual capitalism, would have

combined with improved metal winning and working, to make locks a

promising market. It is quite likely that lock making here would have

started as a local trade, possibly even in conjunction with farming, for

it was not at all uncommon for farmers to augment their income with a

specialist trade and even town dwellers were often both farmers and

artisans.

So at some imprecise time lock making appeared in Wolverhampton,

Willenhall and their environs. The raw materials were near at hand. The

skills were acquired goodness knows how but were soon handed down from

parent to child and from master to apprentice. The market would originally

have been local but it seems that, despite the town's having bad

communications, the market expanded. Locks were small enough to be

transportable by pack horse and waggon. As roads improved and

canals were built, the potential market became wider. But there is nothing

to say why Wolverhampton became a lock making centre when it had the same

starting point as many other places. It must be related to some kind of

local entrepreneurial spirit – and who can say what would explain that?

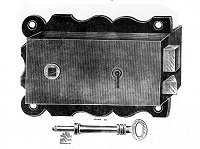

In the earliest lock making times the makers would have been one family

outfits. In the course of time, as the market expanded, firms could grow

larger and some became very large. But even to the end of the lock making

days, there were still one family outfits hard at work.

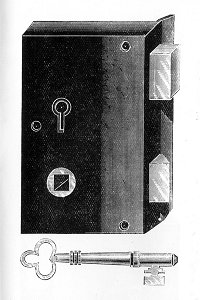

According to J C Tildesley, Locks and Lockmaking, the

"introduction of the lock trade into South Staffordshire took place

as early as the reign of Queen Elizabeth, but it did not flourish very

extensively until the end of the 17th century." His

authority for this account of earlier times is not cited but he gets on

firmer ground with the Hearth Tax of 1660 when, it appears, most of the 84

hearths in Wolverhampton and 95 in Willenhall "were used by the

locksmiths of those times". That might be worth checking a bit

more closely. But Dr. Plot, writing in 1686 also comments that the

"greatest excellence of the blacksmith’s profession in this county

lies in their making of locks for doors, wherein the artisans of

Wolverhampton seem to be preferred to all others …".

This suggests that by the end of the 17th lock making was

well established and was certainly more than a local trade; and that

Willenhall and Wolverhampton both had lock making industries. At that time

to the structure of the trade was, according to Tildesley, beginning to

change. Originally the locks made by the individual manufacturers

"were purchased by chapmen who travelled from place to place with

packhorses. At the commencement of the eighteenth century, however, the

merchants began to establish store rooms in Wolverhampton and Birmingham,

wither the locks and other hardware productions were conveyed by the

smiths, in wallets". (He wrote in 1866 and was able to add that

this system, was "not even yet quite obsolete" and that the

"oldest ware-room in Wolverhampton is that of Messrs. Tarratt, Sons

and Co,. in the Townwell Fold, which has been established considerably

more than a century").

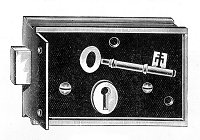

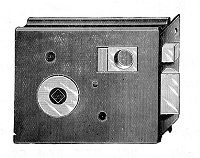

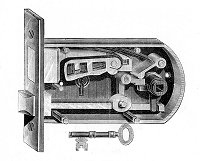

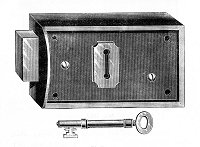

According to Mander (p.143), the Sketchley and Adams trade directory of

1770 shows that the "predominating industry was still that of

lockmaking; no less than 118 names are listed under this head.

Bucklemaking follows, a very close second, with 116". He also deduces

that "lockmaking … had become very specialised. 24 different types

of lock are mentioned – from the ordinary gate lock to the secret bag

lock and the tea chest lock. Often a single person represents an entire

branch of the trade; John Ryley, for example, is the only man to be

described as a letter and baglock maker. George Fox, of Berry Street,

appears as a bitted and swallow bow lock maker, and Thurston Groom, of

Stafford Street, as the only outside box lock maker. The great majority,

however, appear to have been engaged in the manufacture of cabinet locks;

there are three times as many names under this head as under any other,

and, in addition, we find eight cabinet key makers listed".

Of course the brief entries in the directory may cover the fact that

the makers named could and did make other types of lock, the named one

being their preference or speciality. In any case our local lock makers

were renowned for their ingenuity as well as their skills and several

patents were taken out by local men even before the large manufacturers

moved in.

George Price (1856) noted that in 1770 that the numbers of lock making

concerns was:

Wolverhampton 134

Bilston 8

Willenhall 148

By 1855 he records that Willenhall’s slight ascendancy had become a

predominance:

Wolverhampton 110

Bilston 002

Willenhall 340

These raw numbers are not as revealing as they might be – the value

of the trade in each area might have been more informative – but they do

seem to indicate that, during the period covered, Willenhall established

the ascendancy it ever after maintained.

|